I must have hit the backspace button about 20 times before I actually finished this sentence…and I’m still not pleased with how it turned out.

That’s the thing about writers: we are never satisfied. We are always wondering if what we’ve typed was good enough; we sit contemplatively thinking about the receptions our words will get.

As most of you know, I began this profession as a means to keep my mind sharp while I stay at home with my little man. A background as a literature teacher is a blessing and a curse as a writer, although admittedly, the curses are more prevalent in the creative process. What I’m quickly realizing is this: it is far, far easier to be a critic than to create. I use the word critic in its truest sense: a critic can appreciate a work of literature, while simultaneously finding the holes in the theology or break in the story’s cohesion. While I am in the throes of writing my own manuscript, I find the task daunting; often I stop mid-way through a scene realizing that I haven’t developed my characters well enough, or I’ve strayed away from the central purpose in the storyline, or I’ve made the theology too dense, or I’ve made very little sense at all.

It is my background as a literary critic that makes creating to truly difficult. I know just how carefully critics read a piece of literature. I know the art of the black pen and highlighter as well as anyone, shredding an otherwise beautiful piece to pieces: pun intended.

It is in light of this simple truth that I am approaching this review of The Romantic Realist, just as the writers of the collection of essays approached reviewing the life and works of the great C.S. Lewis.

Additionally, just as Phillip Ryken aptly points out about C.S. Lewis, I must make the assertion that I am reviewing this collection of essays of theologians, and I am not a theologian. I am a writer and a literary critic. More than that, I am not even in the same neighborhood as C.S. Lewis. or the rest of these writers. I live somewhere on the other side of town hoping one day I can take a guided tour through his village of winding paved intellectual sidewalks and neatly trimmed philosophical hedges. I have very little to offer in a theological conversation; green in the world of theology and a neophyte in the land of writing. Even though I have very strong religious opinions that are not easily swayed, assuredly, I am not as well versed in the intricacies of theology with which each of these writers is intimately acquainted.

I am a simple visitor in this neighborhood filled with street names like Calvinism, neoorthodox, apologetic reasoning, dispensationalist, soteriology, ecclesiology, and Peligianism. I’ve seen the street names and have a vague idea of who lives on each, but I don’t dine in their homes every evening.

I can say this with confidence: if you are looking for some light reading, do not purchase The Romantic Realist. There is nothing light about this. The Romantic Realist is not exactly a trip to the amusement park. If you are looking for essays to make you think, to help you to examine one of the greatest Christian writers of the 20th century, and to inspire some deep theological conversation about faith, this is probably the book for you…just be sure to have a reference book of theology ready to help you navigate through each of the book’s six essays.

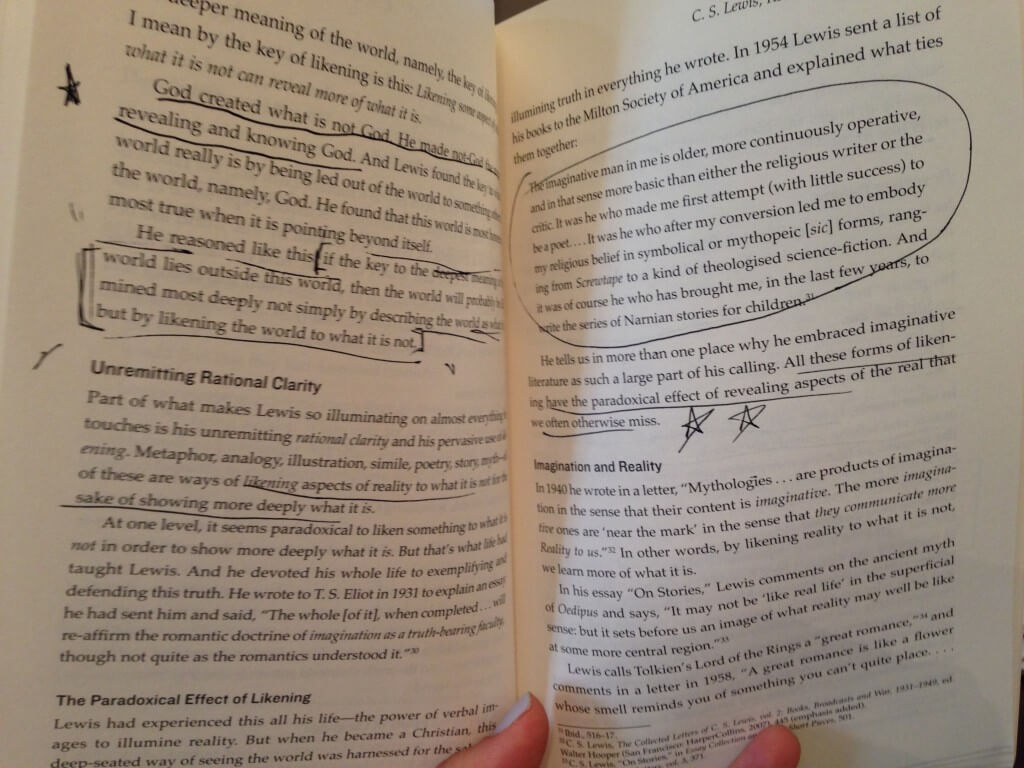

Perhaps my favorite of the six essays was the title essay by John Piper, “C.S. Lewis Romantic Rationalist; How His Paths to Christ Shaped His Life and Ministry.” There was something refreshing about walking with Piper through the life of Lewis as he concludes Lewis to be a “master likener,” allowing for those of us who are not God to understand the nature of God. He simplifies Lewis’ reasoning as a crafter of some of the greatest religious analogies suggesting that each is “the key to the deepest meaning of this world lies outside this world…the world will probably be illumined most deeply not simply be describing the wold as what it is, but by likening the wold to what it is not.” Piper develops this idea further saying that Lewis’ analogies were not created for simple “pleasure,” but for the “power of illumination…to reveal truth.”

Highly skilled in the art of the black pen…

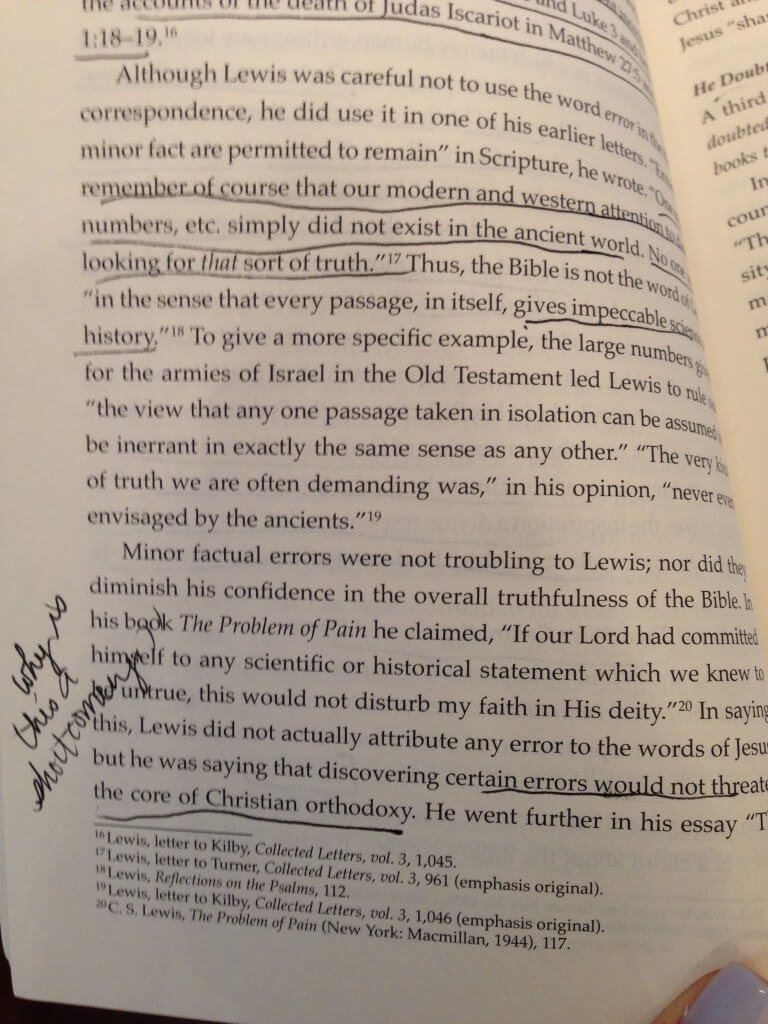

I think part of the reason why I appreciated Piper’s essay was because it didn’t prod into the shortcomings of Lewis’ prose as Phillip Ryken does. He makes some fair points in regards to Lewis’ theology that, Ryken argues, comes dangerously close to suggesting the Bible is not inerrant or uniquely inspired, or wholly historical. Ryken eventually admits that the holes in Lewis’ theology do not take away from the core of his evangelical purpose in his writing. With Ryken’s criticism comes an even deeper appreciation for Lewis’ craft. Still, I was left writing notes in the margins of this particular essay asking, “why is this a shortcoming?” I have always sympathized with Lewis’ assertion that whether Biblical stories of Job or Jonah are historically accurate would not affect the character of Jesus. In other words, whether Jonah literally spent three days in the belly of a fish or metaphorically trapped in a hell of his own making would not make me question my God. God is good, and in my opinion, the story of Jonah is intended to be allegorical. The message of Jonah remains the same.

Shredding someone’s carefully crafted piece to pieces. :(

Again, I am no theologian.

Ryken, like each of the writers, effortlessly weaves a breadth of the work of C.S. Lewis, using each quote to support solid arguments detailing a separate argument whether about his life, work, or imagination. I found Douglas Wilson’s essay to include a dollop of humor with a huge slice of cumbersome theology; unless you know a lot about theological terminology, it may be very difficult to find the humor and you may find yourself wading through the essay looking for a life raft. Help! You may cry out. I am in above my head! Though, I found much of my inspiration to keep writing in his lines as he admits:

“Great writers will have reflected on the reality of {good story writing including high theology}, and great Christian writers tie those reflections in with what God has revealed to us about the story he is telling.”

Ultimately, each of the writers has a specific purpose in their review: to highlight the depth of Lewis’ imagination along with the devotion to his evangelism,

“Lewis desired above all to submit not only his thought but also his whole life to Christ. Some of us may not have sufficiently appreciated the extend to which Lewis was a Christ-intoxicated man,” Vanhoozer admits.

Lewis was a phenomenal writer with ideologies that will last us for centuries to come, but this is not because he was a phenomenal writer. It is because he “was a Christ-intoxicated man.”

Perhaps that is the only lens through which we need to evaluate Lewis’ works, as his goal was simply to evangelize through his writing. The essays were thought provoking, yet dense. This isn’t for the reader who wants something ‘safe.’ Like Aslan, this book isn’t safe, but it is good.

After all, it was Lewis who suggested we are “far too easily pleased.” If you’re willing to do a little work, you’ll find the intellectual musings of these six writers enlightening, illuminating, and even inspiring.

Enter below for your chance to win The Romantic Rationalist.

I think this book sounds fabulous.